Walking for walking’s sake isn’t something that is encountered much in games. An ambling plod tends to lead you to a finishing line or a crowd of slavering zombies. Even walking simulators build to a destination, even if that destination is Mrs Goggins down the post office.

Paradise Marsh is devoid of a destination. Unlike almost every game we’ve played, aside from Proteus perhaps (a comparison that holds some water), Paradise Marsh is about walking, and the things you see on the way. Where you’re walking to is by-the-by.

That aimlessness makes Paradise Marsh refreshing. Once we realised what it was trying to do (or not trying, as the case may be), it felt like a weight had been lifted from us: we could point in any direction and just go. If we wanted to change our minds, we could, and nothing would be lost or compromised. We could play on a whim, and the game would accommodate. Few games can claim to achieve that.

You may be wondering what Paradise Marsh actually is. In very loose terms, it’s along the lines of Alba: A Wildlife Adventure, Bugsnax and Pokemon Snap. It’s a game where wandering the environment comes second only to spotting and collecting creatures in some form. Paradise Marsh is dotted with butterflies, beetles and fireflies, and a journal gets populated by the ones you find and catch. You need more than one of each creature to complete a set – three to five are needed per beastie – and that set also gets represented as a constellation in the sky.

But reducing Paradise Marsh to a creature-collecting game does it a bit of a disservice. You can collect the bugs, but you don’t really have to. Pigeonholing it into that subgenre makes it seem like there is a clear guide-rail to follow in the game, when there isn’t. It’s a faint one to grab hold of if you get mired in the swamp.

We’d categorise Paradise Marsh as a rambler’s toybox. It is entirely procedurally generated. Walking in a given direction leads you through an archipelago of islands, and they pop into existence without a care for things like pop-in. It’s honest about its random generation, and that honesty is helpful to a newly starting player. It tells that player that there isn’t a grand destination to worry about.

While you’re walking, the wonders of Paradise Marsh’s algorithms will toss out a new plaything or minor landmark. A Firewatch-style wooden tower will jut over the horizon, and within it is a handheld console that you can bash buttons on for a while. A giant daisy can be plucked for a game of she-loves-me, she-loves-me-not, and a washing line can be rehung with scattered shorts, shirts and socks. These toys are throughout Paradise Marsh, and tinkering with them is optional. But playing with them as intended – pass a football into the open goal of a shopping trolley, for example – and you’re rewarded with a wink from the designer and a minor fanfare.

The aimless walking has a hint of Proteus about it, as mentioned, and the randomly strewn toys to play with reminded us of Noby Boby Boy. But Paradise Marsh really is its own beast.

The feeling of being lost in the wilderness alone, but without any of the stresses that comes from it, is supported by the day-night cycle, and the sequence of biomes. Keep walking and night will fall. Different creatures appear in the darkness, and monoliths shoot light-beams into the air. These are lighthouses if you want them to be, guiding you through the murk, but they are also a receptacle for the beasts you catch with your net, firing them into the sky so they can be seen as constellations. Once the dawn comes, you keep walking again, and move through various biomes like snow, Japanese water gardens and rainy bayou. Again, creatures are more or less likely to appear based on where you are.

But where Paradise Marsh falters is when it takes on the trappings of a game, and when it tries to apply some meaning to events. As it starts forming into familiar shapes, we liked it least.

Collect creatures for your journal, and those creatures stop appearing in Paradise Marsh’s clever algorithms. Find three bees, and you won’t see a hive again. But start playing Paradise Marsh as a quasi-Pokemon Snap, aiming to ‘catch ‘em all’ and it becomes unsatisfying. The marshes become more and more lonely as the creatures are removed, as the random-creature-generator doesn’t replace them with anything. Hunting for the last creepy-crawly that you need becomes irritating. We left beetles and snails till last, as we hadn’t quite worked out how to catch them, but spent thirty-minutes as the game resolutely refused to present any to us. The walking becomes less relaxing when the tension of collecting is layered like acetate over the top.

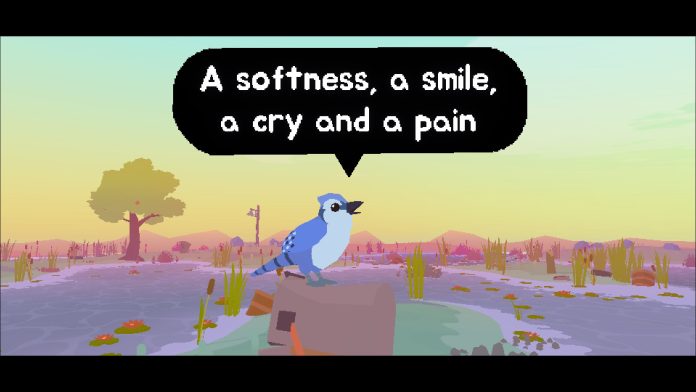

And there’s a dissonance between the calm of Paradise Marsh and how much it wants to talk to you. In the initial parts of the game, messages appear in bottles, and birds perch on signposts, hoping to be chatted to. They deliver vague backstory or abstract poems. Perhaps it’s personal taste or our own expectations for the game, but they interrupted the walking and forced us to engage with the game in a way we didn’t care for. It didn’t help that the prose was so odd and abstract. It’s unfair to the writers, but we would have happily stripped it all out and had a far better time.

But that’s the nature of a good walk. There are distractions – things you hadn’t planned for. Where Paradise Marsh excels is in offering a world that breaks so many of gaming’s golden rules: walk in any direction; do what you want to do; follow the objectives if you feel like it. Paradise Marsh warps and shifts to accommodate whatever you do, and the substance of its genius is that you barely notice.

You can buy Paradise Marsh from the Xbox Store

The last time I “walked for walking’s sake’ in a game I was playing Walk It Out! on the Wii.